A law firm produced 50,000 documents in a complex commercial litigation matter. Their privilege log listed 800 withheld documents with descriptions like "Email regarding legal advice" and "Attorney work product." The opposing counsel moved to compel. The court's response: the descriptions were inadequate, the firm waived privilege on 600 documents, and sanctions followed for the time wasted on the motion practice.

Privilege logs sit at the intersection of two competing interests - protecting confidential communications while ensuring discovery transparency. Get them right, and you preserve critical protections while advancing the case efficiently. Get them wrong, and you face waiver, sanctions, and strategic disadvantage at the worst possible moment.

This guide explains what privilege logs are, why they matter, what makes them adequate under federal and California rules, and how to prepare logs that withstand scrutiny. Whether you're preparing your first privilege log or refining practices for complex ESI productions, you'll find the legal foundations, practical requirements, and common pitfalls courts care about most.

What is a privilege log?

A privilege log is a document listing materials withheld from discovery based on claims of privilege or work-product protection. The log identifies each withheld document or communication with enough detail for opposing parties to evaluate whether privilege applies, but without revealing the privileged information itself.

While Federal Rule 26(b)(5) doesn't use the term "privilege log," courts universally interpret the rule's description requirement as mandating a structured log. In practice, privilege logs typically take the form of spreadsheets or databases with standardized fields for each withheld item.

The log serves as your formal assertion of privilege. It's not optional—it's a procedural requirement tied to your ability to withhold documents. Courts consistently hold that failing to provide an adequate privilege log can result in waiver of the underlying privilege, even when the privilege would otherwise be valid.

What makes privilege logs different from other discovery documents

Privilege logs occupy unique procedural territory. Unlike privilege assertions in depositions (where you state objections on the record) or privilege claims in interrogatory responses (where you note which questions implicate privilege), a privilege log requires affirmative documentation of what you're withholding before anyone asks about specific items.

The log creates a record the court can review if disputes arise. Without adequate logs, courts lack the information needed to resolve privilege disputes efficiently, leading to costly motion practice, in camera reviews, and sanctions that penalize the inadequate party.

Legal foundations of privilege logs

Privilege logs exist because of a fundamental tension in civil litigation: parties must produce relevant documents during discovery, but certain communications remain protected by evidentiary privileges. When you withhold documents based on privilege, procedural rules require you to describe what you're withholding so opposing counsel and the court can evaluate your claims.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(5)(A) creates this obligation. When claiming privilege or work-product protection, you must "expressly make the claim" and "describe the nature of the documents, communications, or tangible things not produced or disclosed - and do so in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable other parties to assess the claim."

The rule serves multiple purposes. First, it prevents blanket privilege assertions without accountability. Second, it gives opposing parties enough information to challenge questionable claims. Third, it provides courts with a workable record for resolving disputes without requiring in camera review of every withheld document.

The privileges that trigger logging requirements

Several evidentiary privileges commonly appear in privilege logs:

Attorney-client privilege protects confidential communications between attorneys and clients made for the purpose of obtaining or providing legal advice. The privilege belongs to the client and covers communications in both directions - client to lawyer and lawyer to client - as long as confidentiality is maintained.

Work-product doctrine protects materials prepared in anticipation of litigation or for trial. This includes documents, tangible things, and mental impressions. Work product has two tiers: ordinary work product (can be discovered upon substantial need) and opinion work product (mental impressions, conclusions, opinions, or legal theories of an attorney, which receive stronger protection).

Common-interest or joint-defense privilege extends attorney-client privilege to communications shared among parties with aligned legal interests, typically co-defendants or co-plaintiffs. The parties must share a common legal interest, and the communication must be made to further that interest.

Other privileges occasionally appear in logs - physician-patient, spousal, clergy-penitent, or statutory privileges under specific regulations. Each privilege has specific legal elements that must be satisfied for protection to apply.

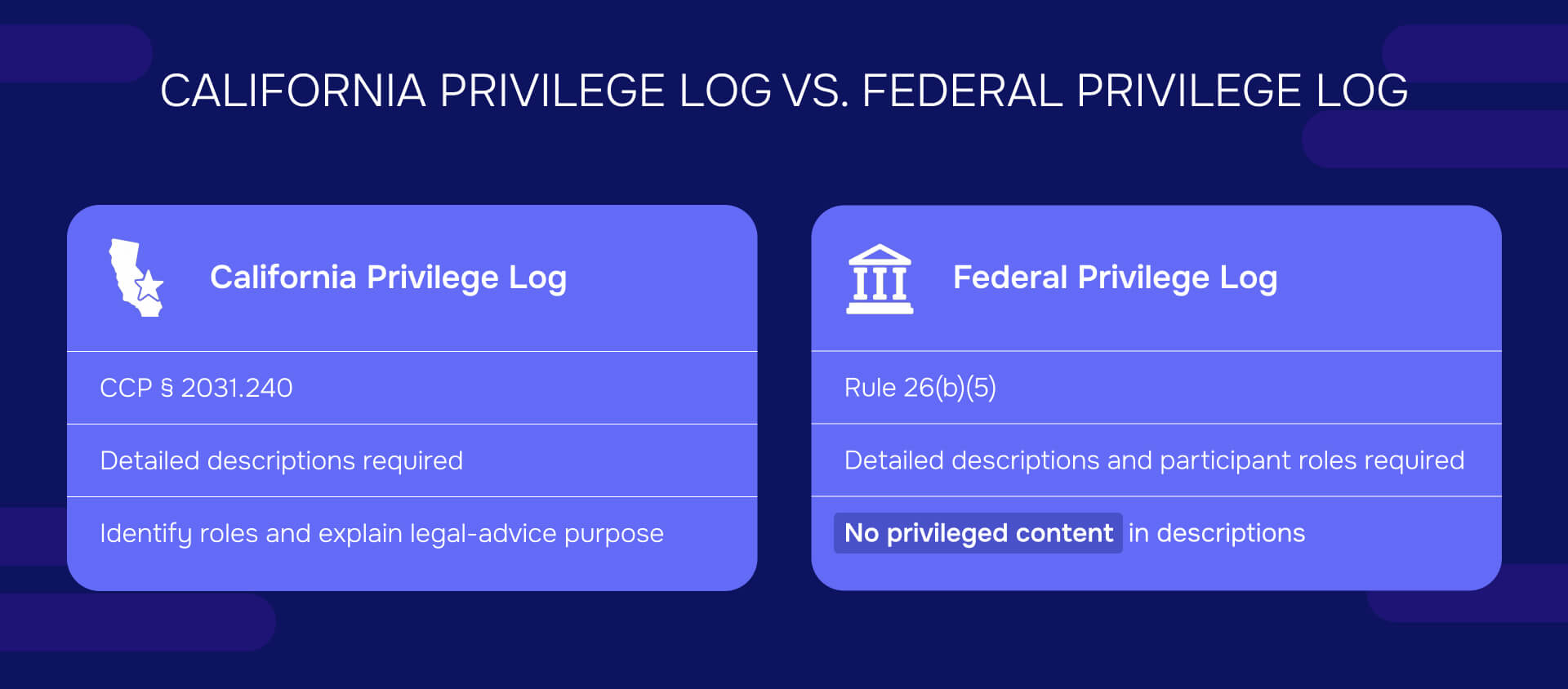

What are California privilege log requirements?

California state courts follow similar principles to federal courts, though the specific procedural rules differ. California Code of Civil Procedure § 2031.240 governs responses to document demands and requires parties to identify withheld documents with specificity.

Under California CCP privilege log requirements, when objecting to document production on privilege grounds, you must provide enough information for the demanding party and court to evaluate the privilege claim. California courts apply the same "sufficient detail" standard that federal courts use - descriptions must be specific enough to allow assessment without revealing privileged content.

California privilege log vs. federal privilege log

The core requirements align between California privilege logs and federal privilege logs. Both jurisdictions require:

- Identification of withheld documents

- The privilege or protection claimed

- Sufficient detail to evaluate the claim

- Descriptions that don't reveal privileged information

California courts have issued numerous decisions addressing privilege log adequacy. Courts regularly reject vague descriptions, require identification of participants' roles (attorney, client, agent), and demand explanations of how the communication relates to legal advice or litigation preparation.

In California state court litigation, the privilege log requirements in CCP § 2031.240 work in conjunction with Evidence Code provisions defining specific privileges. California recognizes attorney-client privilege (Evidence Code §§ 950-962) and work-product protection (Code of Civil Procedure § 2018.030), which form the substantive basis for most privilege log entries.

Practical differences in California practice

California practitioners should note several practical considerations:

Local rules variations: Some California Superior Courts have local rules or standing orders that specify privilege log formats, deadlines, or procedures. Check local rules in the county where your case is pending.

Meet and confer obligations: California's meet-and-confer requirements for discovery disputes apply to privilege log disputes. Before filing a motion to compel, parties must engage in good-faith efforts to resolve disagreements about log adequacy or privilege claims.

Timing: California discovery responses, including privilege logs, typically must be served within 30 days of service of document demands (extendable by stipulation). Federal courts often set privilege log deadlines in case management orders rather than relying on default response periods.

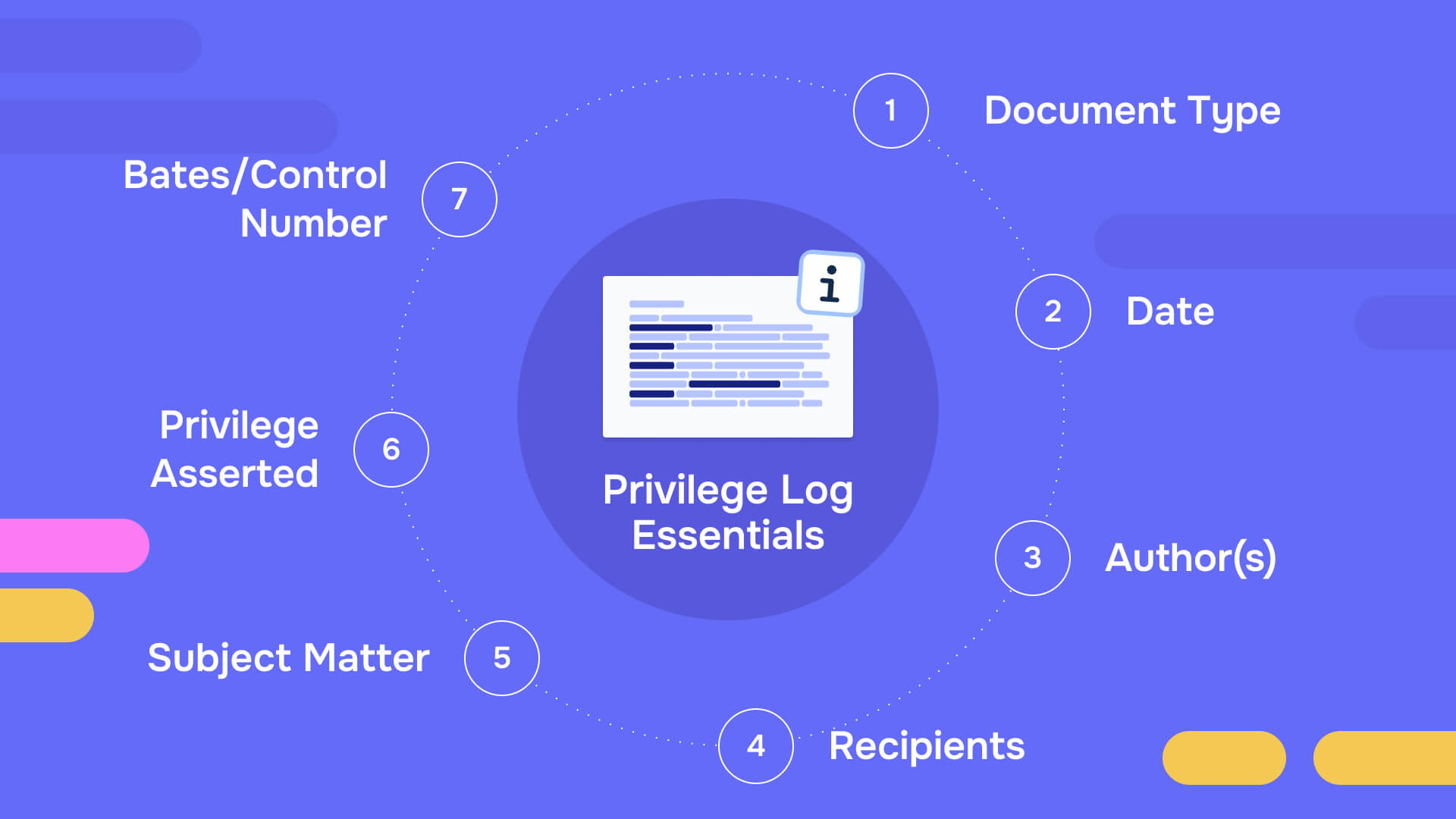

Core elements of a well-drafted privilege log

Courts repeatedly identify the same essential elements in adequate privilege logs. Your log should include these fields for each withheld document:

Document type: Identify whether the item is an email, memorandum, letter, draft agreement, notes, presentation, text message, or other format. Generic descriptions like "document" don't satisfy the requirement.

Date: Provide the date the document was created or the communication occurred. For email chains, use the date of the last message in the chain if withholding the entire thread.

Author(s): Identify who created the document or initiated the communication. Use names, not just "attorney" or "client."

Recipient(s): List all recipients, including those copied or blind-copied on emails. Specify the recipient's role (attorney, client, employee, expert) and relationship to the privilege claim.

General subject matter: Describe the subject in enough detail for evaluation without revealing privileged content. Instead of "legal advice," use "attorney advice regarding patent infringement analysis for Product X licensing negotiation." Instead of "litigation strategy," use "attorney mental impressions regarding witness credibility for upcoming deposition of John Smith."

Privilege asserted: Specify which privilege or protection applies—attorney-client privilege, work-product doctrine (ordinary or opinion), common-interest privilege, or other recognized protection. Explain why the privilege applies if not obvious from the other fields.

Bates or control number: Assign a unique identifier for cross-referencing to document productions, correspondence about specific items, and court proceedings.

How detailed must descriptions be?

The descriptions must walk a careful line. Too vague, and courts find the log inadequate and may order production or impose sanctions. Too detailed, and you risk revealing privileged information, potentially waiving protection.

Courts applying the "sufficient detail" standard require descriptions that allow opposing parties to evaluate whether privilege elements are satisfied. For attorney-client privilege, the description should show: (1) a communication, (2) between attorney and client, (3) made in confidence, (4) for the purpose of obtaining or providing legal advice.

For work product, the description should demonstrate: (1) the material was prepared by or for a party or representative, (2) in anticipation of litigation or for trial, and (3) the specific litigation anticipated.

Bad example: "Email regarding legal matter"Good example: "Email from Jane Smith (in-house counsel) to John Doe (VP Operations) providing legal analysis of potential breach of contract claim by Vendor ABC regarding delivery obligations under Contract 12345"

Bad example: "Attorney work product"Good example: "Draft memorandum prepared by outside counsel analyzing likelihood of summary judgment success on trademark infringement claim in Smith v. Doe, Case No. 23-CV-1234"

Legal standards and case law on adequacy

Courts evaluate privilege log adequacy under the "sufficient detail" standard derived from Rule 26(b)(5). The standard requires enough information for opposing counsel and the court to assess privilege claims without conducting extensive satellite discovery into each withheld document.

What courts consider adequate

Courts find logs adequate when they:

- Identify specific participants by name and role

- Describe the subject matter with enough specificity to understand the communication's purpose

- Explain the connection to legal advice or litigation preparation

- Use consistent privilege categories tied to recognized legal doctrines

- Demonstrate that confidentiality was maintained

What courts reject as inadequate

Courts regularly reject privilege logs containing:

Boilerplate descriptions: Repetitive entries like "email regarding legal advice" across dozens or hundreds of documents suggest inadequate review and description.

Categorical assertions: Claiming privilege for broad categories like "all attorney emails" without document-specific analysis fails the rule's requirements.

Missing role identification: Listing participants without explaining their relationship to privilege (attorney, client, agent, third party) prevents meaningful evaluation.

Vague subject matter: Generic descriptions like "business matters" or "litigation strategy" don't show how the communication relates to legal advice or trial preparation.

Conclusory privilege claims: Stating "attorney-client privilege applies" without explaining why based on the document's characteristics constitutes inadequate description.

Consequences of inadequate privilege logs

When courts find privilege logs inadequate, several consequences typically follow:

Orders to supplement: Courts may grant time to serve a revised log with more detailed descriptions. This is the most lenient remedy but still imposes additional work and cost.

In camera review: Courts may require production of withheld documents for the judge's private review, adding court time and potentially revealing material the court might find non-privileged.

Partial or complete waiver: Courts can find that inadequate logging waives privilege for some or all withheld documents. This is the harshest consequence - you lose protection entirely.

Sanctions: Courts may impose monetary sanctions under Rule 37 or inherent authority for discovery abuse, requiring the inadequate party to pay opposing counsel's fees and costs incurred addressing the deficient log.

Production orders: Courts may simply order production of inadequately logged documents, treating the deficiency as tantamount to abandonment of the privilege claim.

Read also: What does redacted mean in law

Categorical privilege logs and alternative approaches

Traditional privilege logs require document-by-document descriptions. In large ESI productions involving thousands or tens of thousands of withheld documents, creating traditional logs becomes prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Courts have increasingly accepted alternative approaches when circumstances warrant.

What is a categorical privilege log?

A categorical privilege log groups withheld documents into categories based on common characteristics rather than describing each document individually. Instead of 5,000 separate entries, a categorical log might have 20-30 categories with descriptions of the types of documents falling within each category and the number of documents withheld under each category.

For example, a category might be: "Emails between in-house counsel (Jane Smith, John Doe) and business unit managers requesting legal advice regarding compliance with new environmental regulations—143 documents withheld under attorney-client privilege."

When courts permit categorical privilege logs

Courts don't automatically accept categorical logs. Parties typically must show:

Volume justification: The number of withheld documents makes traditional logging unreasonably burdensome relative to the case's stakes and complexity.

ESI complexity: Electronic discovery involving email systems, collaboration platforms, or document repositories where communications are numerous and repetitive.

Cooperation: The parties worked together to develop acceptable categorical approaches through meet-and-confer or ESI protocols.

Court approval: Many courts require advance approval through stipulation or court order before accepting categorical logs.

Sufficient detail within categories: Even categorical logs must provide enough information for privilege evaluation. The category descriptions must be specific about participants, subject matter, and privilege basis.

Metadata-based and hybrid approaches

Some courts accept privilege logs generated from document metadata fields:

- Date/time stamps from email headers

- Author and recipient fields from email systems

- Subject line fields (with appropriate redaction of privileged content)

- Document type metadata from document management systems

Hybrid approaches combine traditional descriptions for key documents with categorical treatment for routine or repetitive communications. For instance, detailed descriptions for substantive legal memoranda but categorical treatment for routine email forwards of those memoranda to additional recipients.

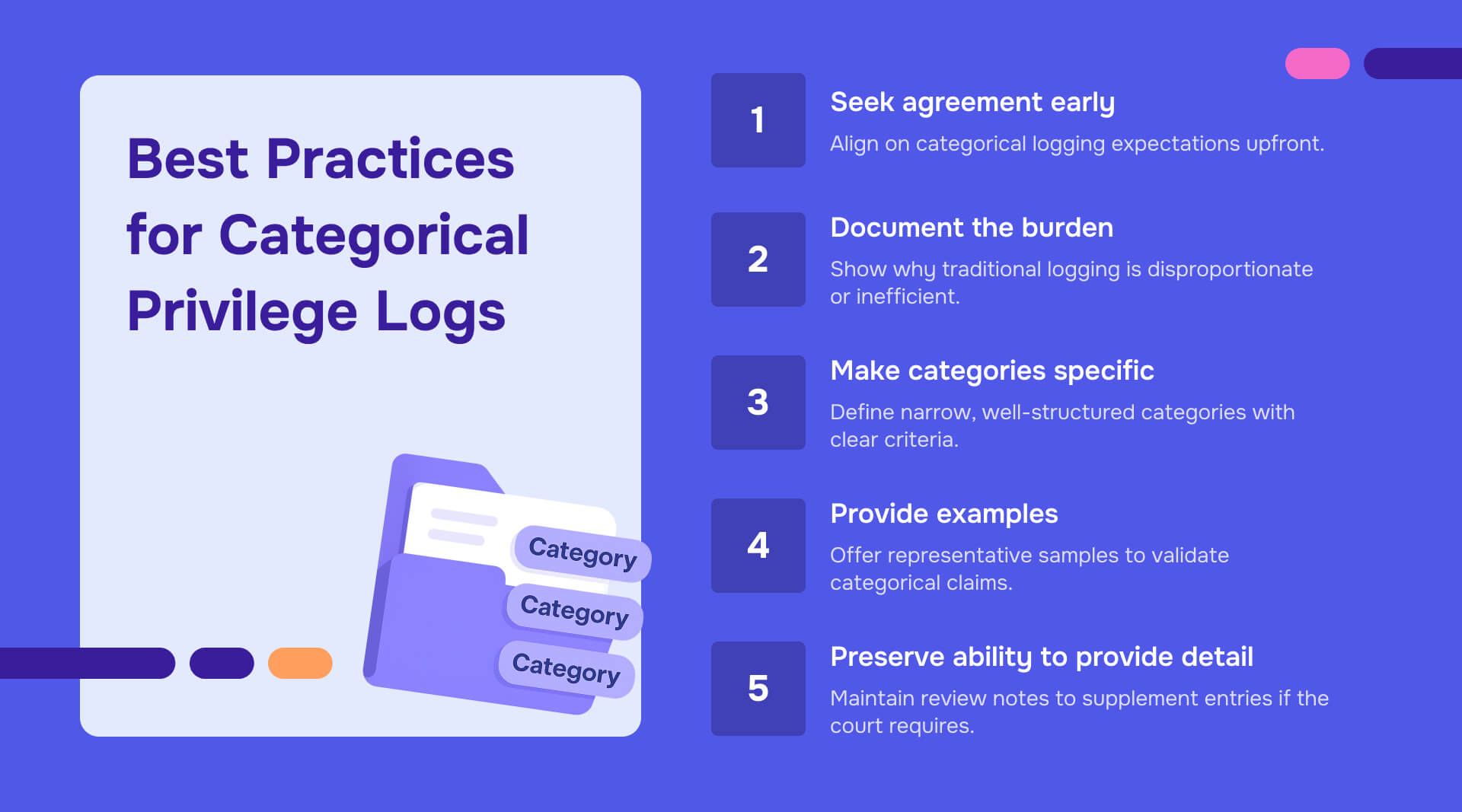

Best practices for categorical privilege logs

If pursuing a categorical approach:

Seek agreement early: Raise the categorical log issue in initial Rule 26(f) conferences or California meet-and-confer sessions before document production begins.

Document the burden: Be prepared to show why traditional logging is unreasonably burdensome—number of documents, cost estimates, proportionality to case stakes.

Make categories specific: Avoid overly broad categories. Categories should be defined by specific combinations of document type, participants, subject matter, and time period.

Provide examples: Offer to produce representative samples of withheld documents within each category for opposing counsel or the court to evaluate whether the categorical descriptions are adequate.

Preserve ability to provide detail: Maintain your underlying document review records so you can provide document-specific descriptions if the court later orders supplementation.

Sources: Sedona Conference commentary on privilege logs

What are the best practices for preparing privilege logs?

Effective privilege log preparation requires planning, consistency, and quality control throughout the discovery process.

Start early with clear protocols

Develop your privilege log approach during case planning, not when production deadlines loom. Address privilege logging in:

Initial disclosures and Rule 26(f) conferences: Discuss the anticipated scope of privilege assertions, expected volume of withheld documents, and whether alternative logging approaches might be appropriate.

ESI protocols and stipulations: Many courts encourage or require ESI agreements addressing privilege log format, deadlines, and procedures for resolving disputes.

Case management orders: Request that case management orders include reasonable privilege log deadlines tied to rolling productions rather than requiring logs simultaneously with first production.

Use consistent privilege labels

Tie your privilege categories to recognized legal doctrines with specific elements:

Attorney-client privilege: Communication between attorney and client for purpose of legal advice, maintained in confidence

Work product - ordinary: Materials prepared in anticipation of litigation, subject to production upon substantial need

Work product - opinion: Attorney mental impressions, conclusions, opinions, or legal theories

Common interest privilege: Communications among parties with shared legal interest, made to further that interest

Avoid vague or unsupported categories like "executive privilege," "proprietary information," or "confidential business information" unless specific statutory or regulatory privileges apply in your jurisdiction.

Draft descriptions that track privilege elements

Structure your subject matter descriptions to demonstrate how privilege elements are satisfied. For attorney-client privilege, show:

- Legal advice was requested or provided

- The communication was confidential

- The participants' roles support privilege (attorney, client, agent acting on client's behalf)

For work product, show:

- Litigation was reasonably anticipated at the time of creation

- The material was prepared because of that anticipated litigation

- The preparer was acting in a legal capacity or at attorney direction

Conduct quality control reviews

Before serving privilege logs:

Consistency check: Review entries for consistent application of privilege categories, description detail, and formatting. Inconsistencies suggest inadequate review and invite challenges.

Spot check substantive claims: For a sample of logged items, verify that the described facts actually support the privilege asserted. Courts penalize parties who assert privilege for clearly non-privileged material.

Third-party communications: Flag any entries involving third parties outside the attorney-client relationship. Communications with vendors, consultants, or business partners may not be privileged even if copying attorneys, unless specific exceptions apply.

Waiver review: Confirm that logged documents weren't previously disclosed in other contexts, shared with adverse parties, or used in ways that might constitute waiver.

Coordinate with opposing counsel

Privilege log disputes waste time and resources. Proactive coordinatio can avoid many conflicts:

Agree on format: Some jurisdictions or courts have preferred formats. Agreeing on column headers, date formats, and organization reduces friction.

Set reasonable deadlines: For rolling productions, build in time between document production and privilege log service. Thirty days after each production tranche is common.

Use meet-and-confer for disputes: Before moving to compel production based on inadequate logs, engage in good-faith meet-and-confer. Many disputes resolve through clarification or supplementation without judicial intervention.

Common privilege log pitfalls and how courts respond

Even experienced practitioners make privilege log mistakes. Understanding common errors helps you avoid them.

Pitfall 1: Logging non-privileged communications

Not every attorney communication is privileged. Business advice, factual investigations, or routine operational communications don't qualify for attorney-client privilege even when attorneys are involved.

Court response: Courts may find that including clearly non-privileged material in logs demonstrates inadequate review, casting doubt on the entire log's reliability. Remedy: review logs to ensure each entry actually satisfies privilege elements.

Pitfall 2: Vague or boilerplate descriptions

Descriptions like "email regarding legal matter" repeated across hundreds of entries tell opposing counsel and the court nothing about whether privilege applies.

Court response: Orders for more specific descriptions, sometimes with examples from the court showing the required detail level. In egregious cases, waiver findings or sanctions. Remedy: provide specific subject matter tied to legal advice or litigation preparation.

Pitfall 3: Failing to identify participants' roles

Listing names without explaining who they are and their relationship to privilege (attorney, client, employee, expert, third-party vendor) prevents evaluation.

Court response: Orders to supplement logs identifying each participant's role and relationship to the asserting party. Remedy: include role identifiers with each name (e.g., "Jane Smith, in-house counsel" or "John Doe, CFO").

Pitfall 4: Inconsistent privilege application

Asserting privilege for some communications but producing similar communications without explanation suggests privilege assertions are arbitrary rather than principled.

Court response: Adverse inferences that withheld documents don't actually contain privileged content, or orders requiring explanation of differential treatment. Remedy: develop clear review protocols and apply them consistently.

Pitfall 5: Missing or incomplete entries

Failing to log all withheld documents, or providing incomplete information for some entries while detailing others, creates appearance of selective privilege assertions.

Court response: Court may infer that incompletely logged items aren't genuinely privileged and order their production. Remedy: quality control processes ensuring every withheld document appears on the log with complete information.

Pitfall 6: Claiming privilege for forwarded materials

Forwarding a privileged document to someone outside the privilege relationship (a business partner, vendor, or other third party) typically waives privilege unless an exception applies.

Court response: Finding of waiver for improperly shared documents, potentially extending to related communications under subject matter waiver doctrine. Remedy: carefully track document distribution and remove improperly shared items from privilege logs.

Privilege logs in government investigations and regulatory proceedings

Privilege logs aren't limited to civil litigation. Government investigations, regulatory enforcement actions, and administrative proceedings often involve privilege assertions requiring logs.

Federal agency investigations

When federal agencies issue subpoenas or document requests (SEC investigations, DOJ inquiries, FTC investigations, agency enforcement actions), recipients can assert privilege and must provide privilege logs similar to civil discovery.

Agency requirements vary. Some agencies have specific privilege log formats or requirements in their procedural rules or guidance documents. Others follow standards similar to Federal Rule 26(b)(5).

State regulatory proceedings

State regulatory agencies conducting investigations - securities regulators, consumer protection agencies, environmental agencies, professional licensing boards—similarly require privilege logs when parties withhold documents on privilege grounds.

California state agencies conducting investigations apply California privilege law and typically expect privilege log requirements similar to California CCP § 2031.240 standards.

Read also: How government agencies can redact sensitive documents?

Government as a party

When government entities are parties to litigation, they may assert privileges including deliberative process privilege, law enforcement privilege, or state secrets privilege in addition to attorney-client and work product.

Privilege logs for government parties must demonstrate that these specialized privileges' elements are satisfied, often requiring more detailed descriptions of deliberative processes, enforcement purposes, or classified nature of information.

Public records requests

Government entities responding to public records requests (FOIA, state public records acts) often must prepare privilege logs explaining why withheld records qualify for privilege exemptions under applicable sunshine laws. These logs serve similar functions to discovery privilege logs but are shaped by public records statutes' specific exemption language.

Sample privilege log structure for California cases

While actual privilege log formats vary by case and court, a well-structured California privilege log typically includes these columns:

Entry number: Sequential numbering for easy reference (1, 2, 3...)

Bates or control number: Unique identifier for each withheld document (ABC00001, ABC00002...) or control number for ESI

Date: Document creation date or communication date

Document type: Email, memorandum, letter, draft agreement, notes, text message, etc.

Author/From: Name and title/role of document creator or message sender

Recipients/To: Names and titles/roles of all recipients, including CC and BCC for emails

Subject matter/Description: Specific description of communication's content without revealing privileged information - must be detailed enough to allow privilege evaluation

Privilege claimed: Specific privilege or protection asserted (attorney-client, work product - opinion, work product - ordinary, common interest)

Basis for privilege: Brief explanation of why privilege applies if not obvious from other fields

Organizing large privilege logs

For privilege logs with hundreds or thousands of entries:

Group related communications: Use subheadings or formatting to group emails in the same chain or documents from the same project.

Provide indexes: For very large logs (1,000+ entries), consider providing an index organized by privilege type, date range, or participant to help reviewers locate relevant entries.

Use consistent date formats: Choose one date format (MM/DD/YYYY or YYYY-MM-DD) and apply consistently throughout.

Alphabetize participant names: When multiple people appear as authors or recipients, list names alphabetically for consistency.

Include explanatory notes: A brief introduction to the log explaining abbreviations, organizational structure, or special circumstances helps reviewers understand your approach.

Redaction and privilege log preparation

Preparing privilege logs often intersects with document redaction. When producing documents with some privileged content redacted, you face dual obligations: the redaction must permanently remove privileged information, and your privilege log must explain what was redacted and why.

The connection between redaction and privilege logs

Partially redacted documents require careful handling:

Privilege log entries for redacted portions: Some courts require separate privilege log entries describing redacted portions within produced documents. Others accept notations on the documents themselves with explanatory text.

Permanent vs. visual redaction: Redactions of privileged material must permanently remove the underlying data. Visual masking (black boxes overlaying text) doesn't actually delete privileged information from the file's metadata and embedded data, creating waiver risks if the underlying data can be recovered.

Redaction logs: In some productions, parties create separate redaction logs explaining each redacted portion's privilege basis, essentially functioning as specialized privilege logs for partial redactions.

Best practices for redaction in privilege contexts

When redacting privileged information from documents you're producing:

Use permanent redaction: Ensure redaction software completely removes privileged text, not just masks it visually. The removed information should not be recoverable through forensic analysis or by removing redaction layers.

Remove metadata: Document metadata (author, creation date, edit history, comments, tracked changes) can contain privileged information. Scrub metadata when producing redacted documents.

Document your redactions: Maintain records of what was redacted and why, supporting your privilege log entries and providing backup if disputes arise.

Consistent redaction standards: Apply the same redaction criteria throughout your production. Inconsistent redaction invites challenges about whether truly privileged material was withheld.

When organizations need to permanently redact privileged information from documents before production - ensuring sensitive attorney-client communications, work product, or other protected material is completely removed rather than just visually masked - specialized redaction tools can ensure compliance with discovery obligations while preserving privilege claims. This becomes particularly important in large productions where manual redaction is impractical and where metadata removal is essential.

Practical checklist for privilege log compliance

Use this checklist when preparing privilege logs:

Before production begins:

- [ ] Discuss privilege log approach with opposing counsel in meet-and-confer

- [ ] Review case management order or local rules for specific privilege log requirements

- [ ] Develop privilege review protocols with clear criteria for each privilege type

- [ ] Choose privilege log format and column structure

- [ ] Set realistic privilege log deadlines in case scheduling

During document review:

- [ ] Mark privileged documents consistently in your review database

- [ ] Capture required information (author, recipients, date, subject, privilege type) during review

- [ ] Flag partial redactions requiring special handling

- [ ] Note any documents with potential waiver issues for secondary review

When preparing the log:

- [ ] Include all required fields (date, author, recipients, subject, privilege, Bates number)

- [ ] Provide specific descriptions demonstrating privilege elements

- [ ] Identify participants by name and role

- [ ] Use recognized privilege categories tied to legal doctrines

- [ ] Check for consistent application across similar documents

Quality control before service:

- [ ] Spot check sample entries to verify substantive privilege claims

- [ ] Review for boilerplate or vague descriptions

- [ ] Confirm all withheld documents appear on the log

- [ ] Verify no privileged information disclosed in descriptions

- [ ] Check for inadvertent waiver indicators (prior disclosure, third-party sharing)

After service:

- [ ] Maintain underlying review records supporting log entries

- [ ] Track any challenges or objections to specific entries

- [ ] Update logs for rolling productions with new withheld documents

- [ ] Engage in meet-and-confer to resolve disputes before motion practice

Take action on privilege log compliance

Privilege log preparation demands attention to procedural requirements, substantive privilege law, and practical efficiency. Start with these priorities:

Assess your approach early: During initial case planning, evaluate the likely volume of privileged materials, discuss privilege log expectations with opposing counsel, and build reasonable timelines into case scheduling.

Develop clear protocols: Create privilege review guidelines that define when each privilege type applies, what information reviewers must capture, and what description detail satisfies court requirements.

Invest in quality control: Spot check privilege log entries before service to catch vague descriptions, missing role identifications, inconsistent privilege application, or potential waiver issues.

Courts have little patience for inadequate privilege logs. They waste party resources, burden judicial dockets, and suggest inadequate attention to discovery obligations. The investment in proper privilege logging - clear protocols, detailed descriptions, and quality control - protects your privilege claims while demonstrating professionalism that serves clients' interests and maintains standing with courts and opposing counsel.

When privilege log preparation intersects with document production, remember that partial redactions and privilege assertions both require careful handling to avoid waiver. Proper permanent redaction of privileged material, combined with accurate privilege logging, creates a defensible record of your discovery compliance.

Need to redact privileged information from documents before production? When preparing documents for discovery, ensure sensitive attorney-client communications and work product are permanently removed, not just visually masked. Try Redactable for free and experience AI-powered permanent redaction with guaranteed metadata removal, or book a demo to see the tool in action.