A law firm reviewing loan files for a client transaction. A SaaS vendor processing payment data for a fintech partner. A corporate treasury team sharing customer account details with a marketing agency.

All three are handling NPPI - nonpublic personal information - and most don't realize it until a breach notification deadline hits or a regulator asks to see their safeguards program.

Here's what catches organizations off guard: GLBA's NPPI regime covers far more than traditional banks. Fintechs, auto dealers, certain advisors, payment processors, and even law firms acting as service providers all fall within scope. The FTC now requires non-bank financial institutions to notify it within 30 days of certain breaches involving NPPI. And state privacy laws are increasingly circling around financial data that GLBA historically carved out, creating new compliance layers.

The regulatory gap isn't whether you handle personal information - it's whether you recognize when that information becomes non-public personal information under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, triggering specific security, privacy, and breach notification obligations.

This guide explains what is NPPI, where it shows up in real-world workflows, who must protect it, and how to avoid the compliance failures that lead to regulatory scrutiny and six-figure penalties.

What does NPPI stand for? The GLBA definition explained

NPPI stands for non-public personal information, a term defined under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) and its implementing regulations. You'll also see it written as "NPI" or "nonpublic personal information" in regulatory guidance—they refer to the same concept.

The core GLBA definition has two components:

1. Personally identifiable financial information (PIFI)

This includes any information:

- A consumer provides to obtain a financial product or service (loan applications, account opening forms)

- That results from a transaction involving a financial product or service (account balances, payment history, transaction logs)

- Otherwise obtained in connection with providing a financial product or service (credit reports, risk scores, fraud assessments)

- Lists, descriptions, or groupings of consumers derived from the above information (customer lists based on transaction patterns, segmentation models)

2. That is not publicly available

Information is not NPPI if it's lawfully available from:

- Government records (property deeds, court filings, business registrations)

- Widely distributed media (phone directories, news articles, public websites)

- Required public disclosures (SEC filings, regulatory reports)

The practical test: if an individual's name, account number, transaction history, or financial details are tied together and not available through public sources, you're likely dealing with NPPI.

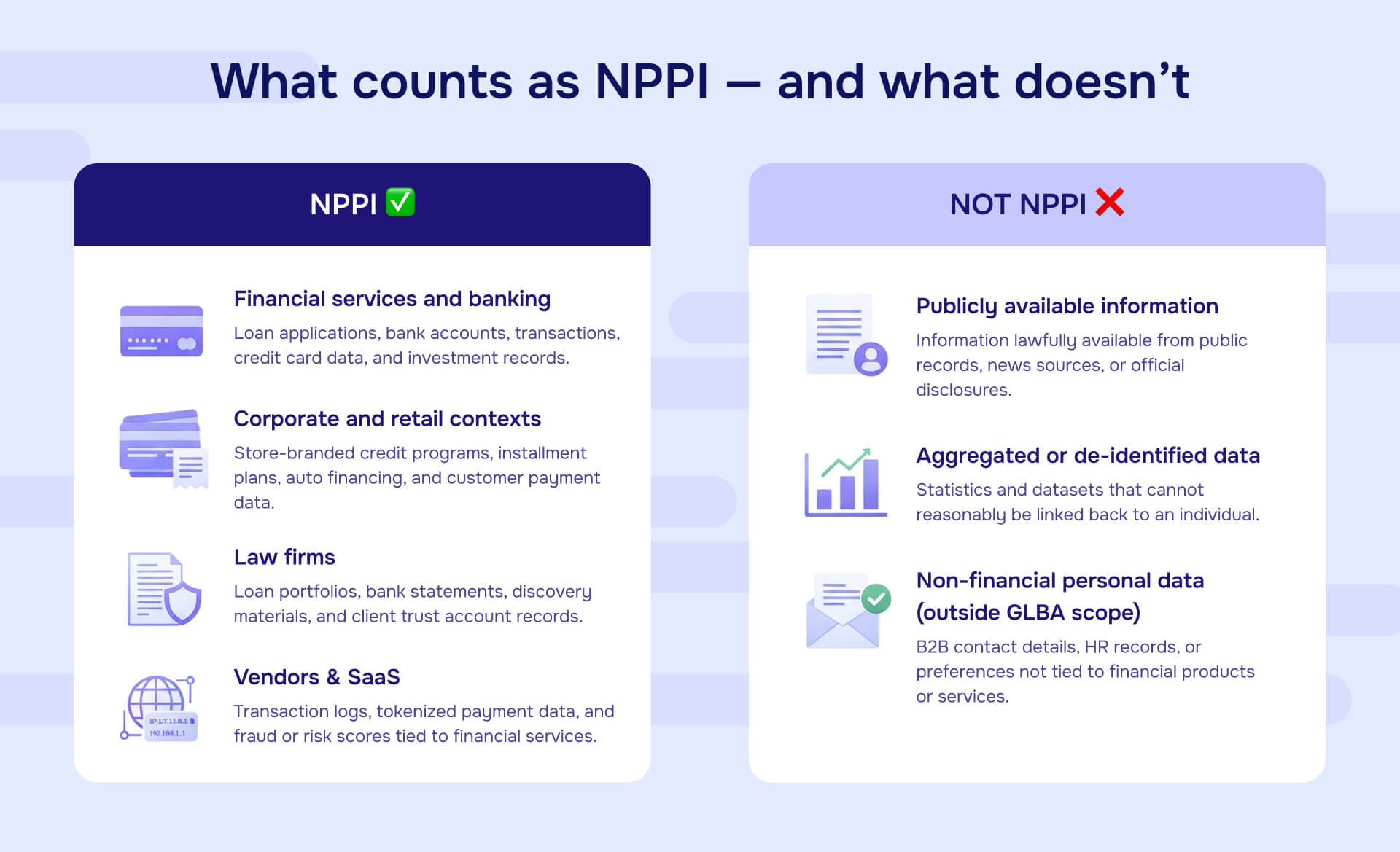

Non-public personal information examples: what counts as NPPI?

Understanding NPPI in theory is one thing. Recognizing it in your actual systems and workflows is another.

Financial services and banking

- Loan applications with income, employment history, SSN, credit scores

- Bank account numbers, balances, and transaction histories

- Credit card numbers and payment details

- Mortgage documents showing borrower financial information

- Investment account statements and portfolio holdings

Corporate and retail contexts

- Store-branded credit program applications and account data

- Installment payment plans with customer financial details

- Loyalty program accounts tied to payment card data

- Auto financing applications and payment histories

- Customer lists that include account numbers or payment information

Law firm and professional services

- Loan portfolios and securitization documents in M&A due diligence

- Bank statements and financial records in discovery

- Debt collection files with account details

- Credit reports obtained for litigation or transactions

- Client trust account information

Vendor and SaaS operations

- Tokenized payment card data linked to customer names

- Transaction logs for financial service clients

- Risk scores or fraud flags generated from financial data

- Payment processing records showing account details

What is NOT considered non-public personal information

Publicly available information:

- Information from government records already disclosed (property ownership, business licenses)

- Data published in news articles, directories, or public websites

- SEC filings and other mandatory public disclosures

Aggregated or de-identified data:

- Statistics that don't identify individuals ("10% of borrowers were late on payments")

- Anonymized datasets where individuals cannot be reasonably re-identified in context (not just stripped of direct identifiers, but truly anonymized such that re-identification is not reasonably possible given available data and technology)

Non-financial personal data (outside GLBA scope):

- Work email addresses in B2B contact lists (may still be "personal data" under GDPR or CCPA, but not NPPI)

- Employee HR records unrelated to consumer financial services

- Marketing preferences not tied to financial products

The gray areas that trip up compliance

Derived and combined data:

A bank's internal fraud detection system flags high-risk customers based on transaction patterns. Is that risk score NPPI, even though it's generated internally and never directly provided by the customer?

Yes. Internal risk scores, fraud flags, or segmentation models built from NPPI are generally treated as NPPI themselves. The fact that you derived the data doesn't make it less sensitive - it often makes it more sensitive because it reveals financial behavior patterns.

Similarly, publicly available information combined with NPPI remains NPPI. A lender pulls public real estate records showing a property's assessed value, then combines it with the bank's internal appraisal and the borrower's loan-to-value ratio. That combined dataset is NPPI, even though one component started as public information.

Metadata and logs:

Your payment processing system generates transaction logs showing dates, amounts, and account identifiers for compliance monitoring. No customer will ever see these logs—they're purely internal. Are they NPPI?

Yes. Transaction logs, system access records containing customer account numbers, and email metadata revealing financial relationships all qualify as NPPI because they're "obtained in connection with" providing financial services. The fact that they're backend operational data doesn't exempt them from GLBA safeguards.

This trips up organizations during vendor integrations and system audits. A fintech company shares transaction logs with a cloud analytics provider for performance monitoring, assuming "it's just technical data." Those logs contain NPPI, triggering vendor management and contract requirements under the Safeguards Rule.

Device IDs and digital identifiers:

A mobile banking app collects device IDs, IP addresses, and session tokens to prevent fraud and provide secure access. These aren't traditional financial identifiers like account numbers - they're technical infrastructure data. Do they count as NPPI?

Often, yes. Device IDs, IP addresses, and online identifiers linked to financial products (online banking sessions, mobile payment apps, investment platform access) typically fall within NPPI because they're "obtained in connection with" providing financial services. They become part of the customer's financial profile, especially when used for authentication, fraud detection, or transaction monitoring.

The compliance risk: organizations treat these identifiers as "just tech data" and share them freely with analytics vendors, advertising partners, or third-party security tools without recognizing they're handling NPPI subject to GLBA sharing restrictions and safeguards requirements.

These gray areas matter because GLBA's safeguards requirements apply to all "customer information," defined as any records containing NPPI. Incomplete classification leads to incomplete protection.

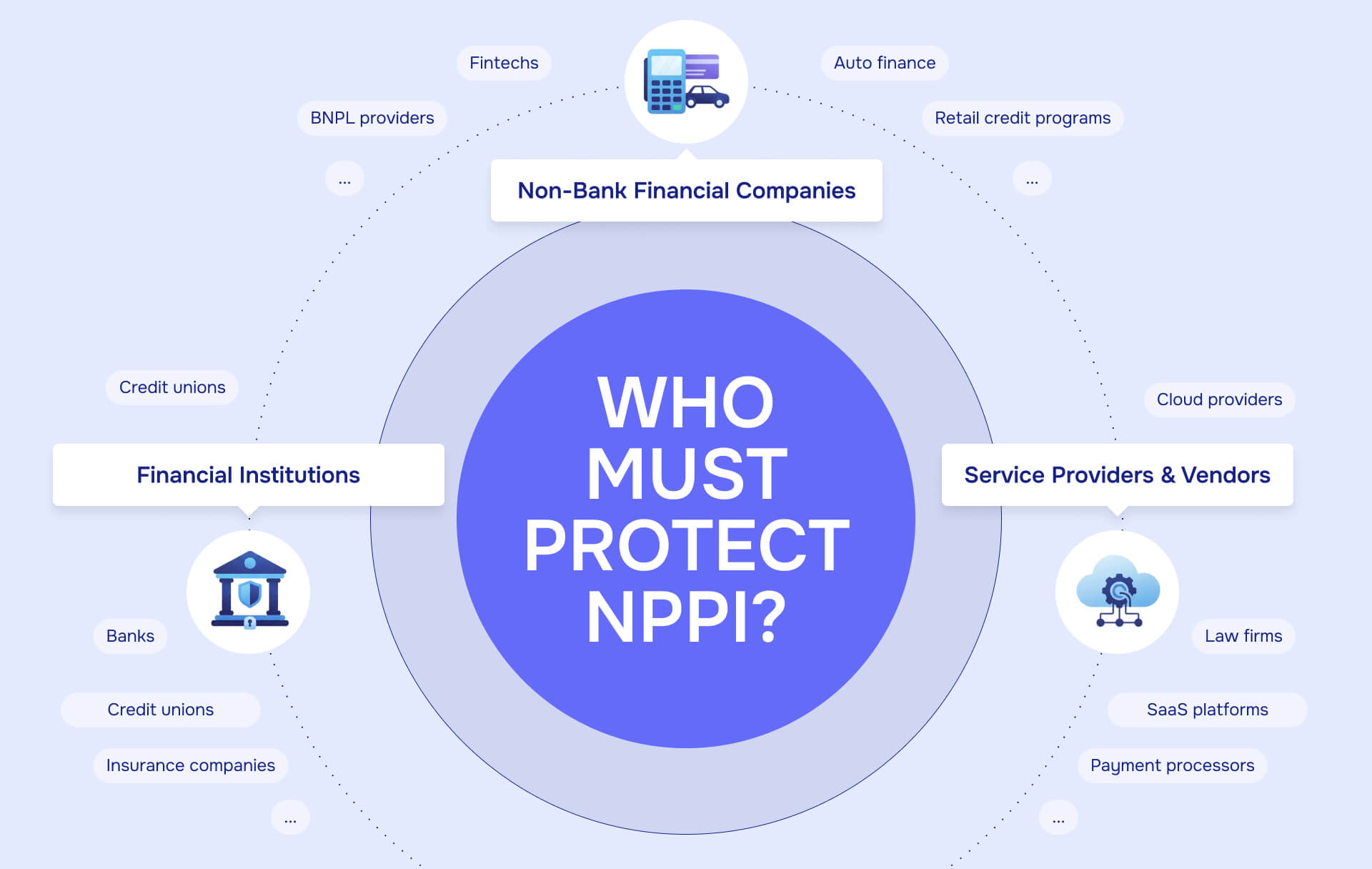

Who must protect NPPI? (It's not just banks)

GLBA's "financial institution" definition is deliberately broad: any company significantly engaged in financial activities. This sweeps in many organizations that don't think of themselves as financial services companies.

Which organizations are directly covered as financial institutions?

Traditional financial services:

- Banks, credit unions, savings associations

- Securities firms, investment advisors, insurance companies

- Mortgage lenders and brokers

- Credit card issuers and consumer finance companies

Non-bank financial institutions:

The following entities may be covered as "financial institutions" under GLBA if they are significantly engaged in financial activities. Whether a specific organization falls within GLBA's scope depends on the nature and extent of its financial activities:

- Fintechs offering payment processing, lending, or investment services

- Buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) providers

- Retailers with store-branded credit programs

- Auto manufacturers with captive finance arms

- Real estate settlement services

- Debt collectors and credit repair services

- Check cashing businesses and money transmitters

Service providers and vendors (covered by contract and regulation)

Even if you're not a "financial institution" yourself, GLBA and the FTC Safeguards Rule impose obligations on service providers that handle NPPI on behalf of financial institutions:

Law firms:

- Handling loan portfolios, securitizations, or M&A due diligence involving financial institutions

- Managing litigation with NPPI in discovery

- Acting as service providers under client contracts that require GLBA-compliant safeguards

Technology vendors and cloud providers:

- Cloud storage providers hosting NPPI for financial clients

- Data analytics platforms processing financial transaction data

- Payment processors and gateway providers

- Regtech and compliance software vendors

- CRM and marketing automation platforms used by financial institutions

Other professional services:

- Accounting firms auditing financial institutions

- Consultants advising on financial products or operations

- Third-party administrators for benefit plans with financial components

The practical consequence: if you receive NPPI from a financial institution client or process it on their behalf, you're contractually - and often regulatorily - equired to implement appropriate safeguards, even if GLBA doesn't directly regulate your primary business.

What are your obligations when handling NPPI?

Understanding what NPPI is matters only if you know what you must do with it. GLBA and the FTC's implementing rules impose three categories of obligations.

1. Privacy notices and sharing restrictions

GLBA's Privacy Rule requires financial institutions to:

Provide clear privacy notices:

- Initial notice when a customer relationship begins

- Annual privacy notices explaining what NPPI is collected, how it's used, and with whom it's shared

- Opt-out notices if NPPI will be shared with non-affiliated third parties for certain purposes

Restrict sharing for marketing:

- Financial institutions cannot share account numbers or access codes with non-affiliated third parties for marketing purposes

- Other NPPI can be shared only after providing opt-out rights, subject to statutory exceptions

Honor statutory exceptions:

- Sharing is permitted without opt-out for processing transactions, preventing fraud, responding to legal requirements, and certain other specified purposes

For law firms, vendors, and corporate service providers: these obligations typically flow through contracts. Your financial institution clients will require you to maintain confidentiality and limit use of NPPI consistent with their own privacy commitments.

2. Information security safeguards

The FTC Safeguards Rule requires covered financial institutions to develop, implement, and maintain a comprehensive written information security program designed to protect customer information (any records containing NPPI).

Required elements include:

Risk assessment:

- Identify reasonably foreseeable internal and external risks to the security, confidentiality, and integrity of customer information

- Assess the sufficiency of existing safeguards for controlling identified risks

Access controls:

- Limit access to customer information to authorized individuals with a legitimate business need

- Implement multi-factor authentication for systems accessing customer information

- Encrypt customer information in transit and at rest (or demonstrate equivalent protections)

Security monitoring:

- Continuously monitor systems and detect unauthorized access attempts

- Implement logging and audit trails for customer information access

- Test security systems regularly through penetration testing or vulnerability assessments

Vendor management:

- Exercise due diligence in selecting service providers capable of maintaining appropriate safeguards

- Require service providers by contract to implement and maintain safeguards for customer information

- Periodically reassess vendor security practices

Incident response:

- Establish procedures to detect, respond to, and recover from security events

- Report certain security events to the FTC within 30 days (for covered non-bank financial institutions)

- Notify affected customers as required under applicable breach notification laws

Ongoing oversight:

- Designate a qualified individual to oversee the information security program

- Provide security awareness training to all personnel

- Update the program as technology, threats, and business operations change

3. Breach notification and regulatory reporting

Beyond the general Safeguards Rule, covered non-bank financial institutions must now notify the FTC within 30 days of discovering a "notification event" - a security breach affecting the NPPI of at least 500 consumers.

State laws add another layer: most states have breach notification statutes requiring notification to affected individuals and sometimes to state regulators when personal information (which often includes NPPI) is compromised.

The compliance trap: NPPI breaches often trigger multiple notification obligations (FTC reporting, state breach notification, contractual notice to financial institution clients) with different timing requirements and definitions. Organizations that don't recognize NPPI as a distinct category miss these layered duties.

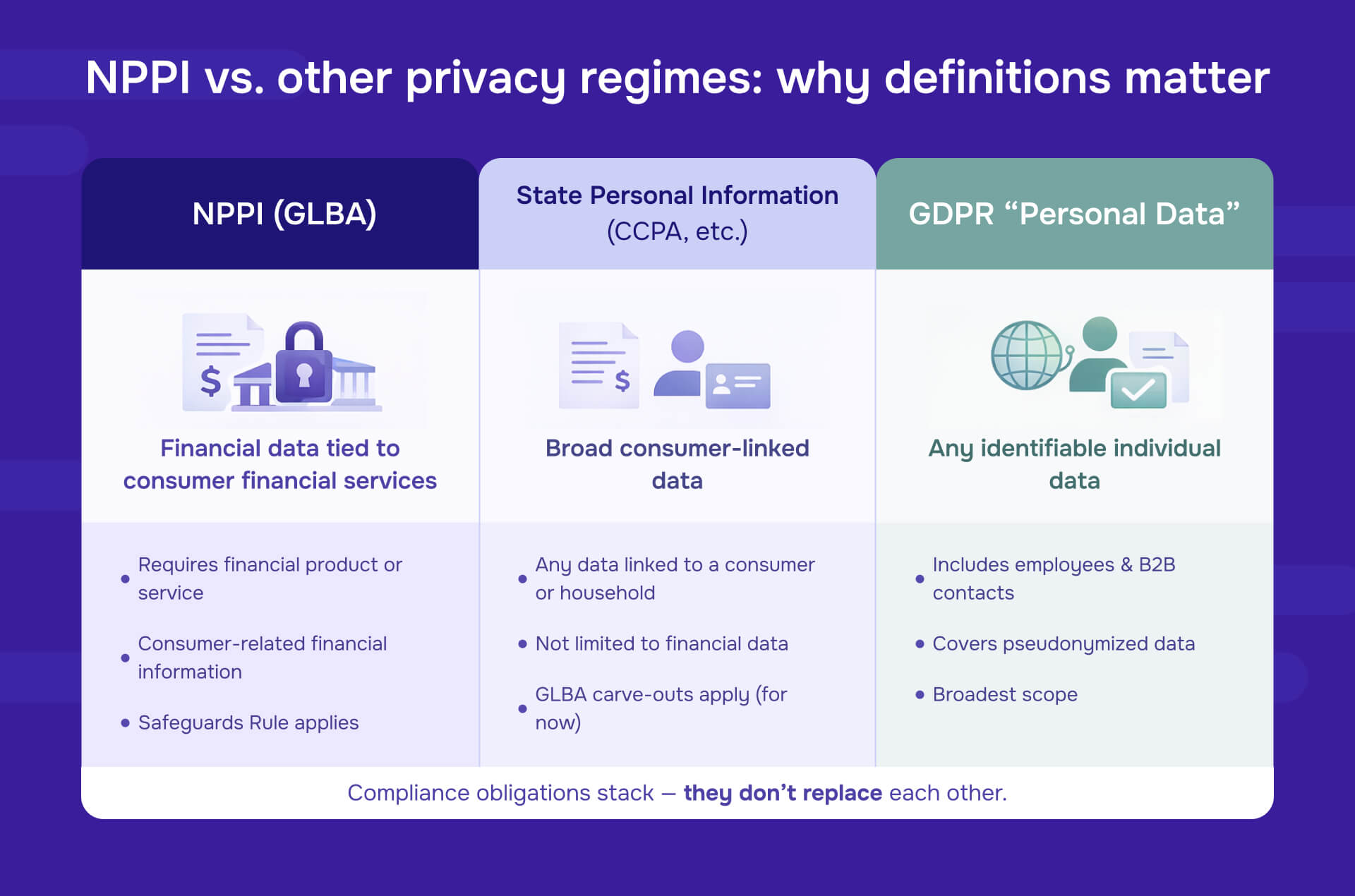

NPPI vs. other privacy regimes: Why definitions matter

One of the most common compliance mistakes is treating NPPI as synonymous with "personal information" under state privacy laws or "personal data" under GDPR-style regulations. It's not.

NPPI is narrower than state "personal information"

State privacy laws like the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) define "personal information" broadly to include any information that identifies, relates to, or could reasonably be linked to a particular consumer or household—regardless of whether it's financial.

Key differences:

- NPPI requires a connection to a financial product or service; state "personal information" does not

- Many state laws exempt information already covered by GLBA from certain requirements, creating partial overlap but not complete alignment

- The CFPB has encouraged states to regulate financial data more fully, suggesting the GLBA carve-outs may narrow over time

Practical consequence: A dataset may be NPPI under GLBA (triggering Safeguards Rule requirements) AND "personal information" under state law (triggering consumer rights like access, deletion, and opt-out of sale). Compliance with one regime doesn't satisfy the other.

NPPI is much narrower than GDPR "personal data"

Under GDPR and similar international frameworks, "personal data" means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. This includes:

- Professional contact details (work email, office phone)

- Employee records unrelated to consumer financial services

- Marketing preferences and behavioral data

- Even pseudonymized data if individuals can be re-identified

NPPI, by contrast, requires both personally identifiable information and a connection to financial services.

Practical consequence for multinational organizations: European employee HR data, customer service records, and B2B contact lists are "personal data" subject to GDPR but typically not NPPI. Conversely, U.S. consumer loan files are NPPI under GLBA but may or may not trigger GDPR depending on data subject location and processing context.

The patchwork problem: duties stack, they don't substitute

Scholars and regulators have criticized GLBA's protections as comparatively limited - especially regarding consumer control, data minimization, and transparency. This has led to:

- State legislatures passing broader privacy laws that don't defer entirely to GLBA

- The CFPB openly suggesting that states can and should regulate financial data more comprehensively

- A patchwork where sophisticated organizations must navigate GLBA + state privacy laws + sector-specific rules (HIPAA for health-related financial data, FCRA for credit reporting, etc.)

The operational reality: Don't assume that GLBA compliance exempts you from other privacy obligations. Treat NPPI as a baseline for financial data, not a ceiling.

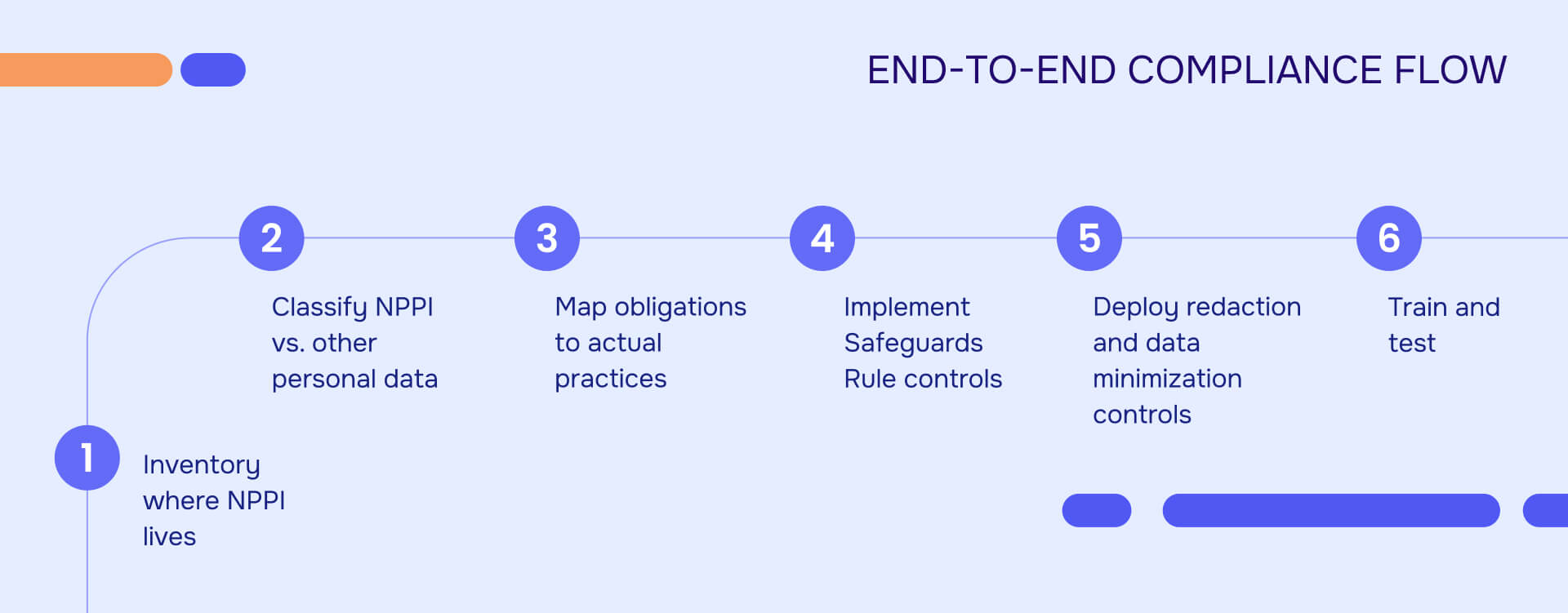

Practical NPPI compliance checklist

Compliance with NPPI requirements isn't a one-time legal review - it's an operational discipline that spans data governance, security, contracts, and training.

Step 1: Inventory where NPPI lives

Map every system, platform, and workflow where NPPI appears:

- Core financial systems (loan origination, account management, payment processing)

- Shared drives and document repositories

- Email archives and collaboration platforms (Slack, Teams, shared inboxes)

- Deal rooms and virtual data rooms (M&A, due diligence)

- Discovery platforms and litigation hold systems

- CRM and marketing automation tools

- Cloud storage and backup systems

Don't stop at structured databases. NPPI often hides in unstructured data: email attachments, meeting notes, spreadsheets, scanned documents.

Step 2: Classify NPPI vs. other personal data

Tag datasets by regulatory category:

- NPPI under GLBA: Financial information about consumers, not publicly available

- Personal information under state law: May include NPPI plus broader categories

- Protected health information (PHI) under HIPAA: Health-related financial data (medical billing, health insurance) may be both NPPI and PHI

- Other regulated data: Credit report information under FCRA, biometric data under state biometric laws, etc.

Classification drives control selection. NPPI requires Safeguards Rule protections; PHI requires HIPAA Security Rule controls; some data requires both.

Step 3: Map obligations to actual practices

For each NPPI data store or process:

- Privacy notices: Do your notices accurately describe collection, use, and sharing? Do you provide required opt-outs?

- Sharing practices: Are you sharing NPPI with non-affiliated third parties? If so, under what exception? Have you obtained opt-out consent where required?

- Contracts: Do vendor agreements and service provider contracts include GLBA-compliant safeguards language? Do you have audit rights?

- Access controls: Is NPPI restricted to authorized personnel? Do you use multi-factor authentication?

- Encryption: Is NPPI encrypted in transit and at rest?

- Incident response: Do you have procedures to detect, respond to, and report NPPI breaches within required timelines?

Step 4: Implement Safeguards Rule controls

Align your information security program with FTC Safeguards Rule requirements:

- Designate a qualified individual to oversee the program

- Conduct periodic risk assessments

- Deploy access controls, encryption, and monitoring

- Test systems through penetration testing or vulnerability scans

- Manage vendor risk through due diligence and contractual requirements

- Train all personnel who handle customer information

- Update the program as threats and operations evolve

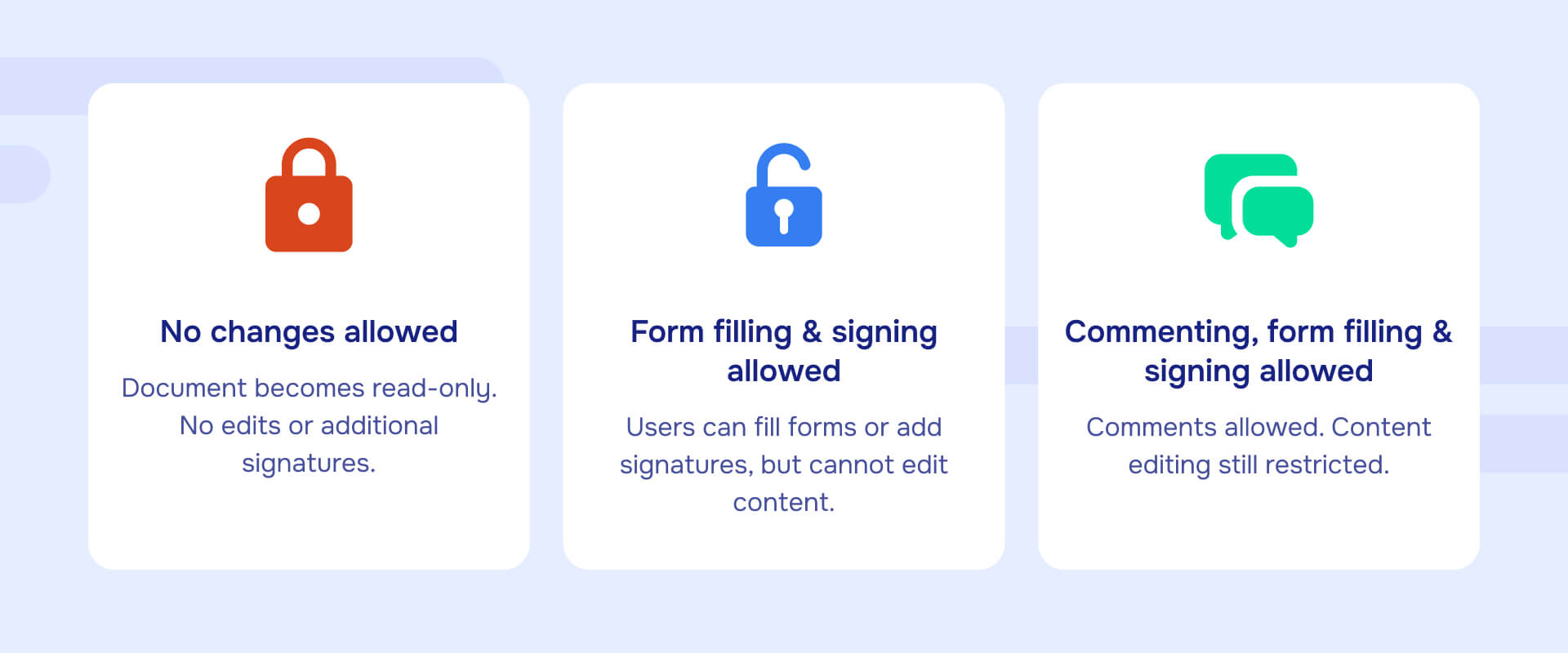

Step 5: Deploy redaction and data minimization controls

NPPI often appears in documents that must be shared externally: discovery responses, due diligence materials, regulatory submissions, customer service records.

The compliance gap: Visual redaction (black boxes, highlighting, strikethrough text) doesn't remove NPPI from documents. Underlying text and metadata remain recoverable, creating ongoing GLBA violations and breach risk.

What NPPI compliance requires:

- Permanent removal of NPPI from documents before sharing

- Metadata stripping (author names, edit history, document properties, embedded comments)

- Audit trails showing what was redacted, when, and by whom

Implementation for high-volume workflows:

Organizations handling high volumes of NPPI—law firms managing discovery, financial institutions responding to regulatory requests, vendors processing customer data—need professional redaction tools or APIs that:

- Automatically detect NPPI (account numbers, SSNs, financial identifiers)

- Permanently remove content from document structure, not just mask it visually

- Strip metadata and hidden data

- Generate redaction certificates and audit trails

- Integrate into existing workflows (document management systems, CRM platforms, regulatory pipelines)

Redaction APIs enable automated, policy-driven redaction across thousands of documents without manual review - essential for scaling NPPI protection without introducing manual error.

Step 6: Train and test

GLBA compliance fails when staff don't recognize NPPI in real-world contexts:

- Train legal, finance, compliance, and operations teams to identify NPPI

- Provide scenario-based training (what to do when NPPI appears in an email, a scanned document, a customer service ticket)

- Conduct tabletop exercises simulating NPPI breaches to test incident response

- Run "red team" tests where internal auditors attempt to access NPPI improperly

Document everything: Regulators assess not just whether you have policies, but whether you operationalize and test them. Training records, risk assessments, vendor due diligence files, and incident response logs demonstrate a mature compliance program.

Where NPPI compliance breaks down - and how to fix it

Common failure point 1: Treating NPPI like any other personal data

The mistake: Organizations apply generic data security practices without recognizing NPPI's specific requirements (Safeguards Rule, privacy notices, FTC breach reporting).

The fix: Tag NPPI as a distinct category in data inventories, apply GLBA-specific controls, and train teams on the difference between NPPI and broader "personal information."

Common failure point 2: Ignoring metadata and hidden data

The mistake: Redacting visible NPPI (account numbers, SSNs) from documents but leaving it in metadata, version history, or embedded objects.

The fix: Use redaction tools that strip metadata and permanently remove text—not just visually mask it. Verify that "redacted" documents don't leak NPPI through file properties, tracked changes, or hidden layers.

Common failure point 3: Inadequate vendor oversight

The mistake: Assuming that cloud providers, SaaS vendors, or law firms handling NPPI "must be compliant" without due diligence, contractual safeguards, or periodic reassessment.

The fix: Exercise due diligence before engaging service providers, require GLBA-compliant contract language, and periodically audit vendor practices. Document your vendor risk management process.

Common failure point 4: No clear breach notification playbook

The mistake: Discovering an NPPI breach and scrambling to determine notification obligations, missing FTC's 30-day deadline or state law requirements.

The fix: Build a breach response playbook that identifies:

- When an incident qualifies as a "notification event" under FTC rules

- State breach notification triggers and timelines

- Contractual notification requirements to financial institution clients

- Who makes notification decisions and drafts required notices

Test the playbook with tabletop exercises so response is automatic, not improvised.

What makes NPPI different from other privacy acronyms?

NPPI - non-public personal information - represents a specific regulatory category with concrete obligations under GLBA, the FTC Safeguards Rule, and FTC breach notification requirements.

Here's what to remember:

- NPPI is narrower than "personal information" under state law or "personal data" under GDPR. It requires both personally identifiable information and a connection to financial products or services. But compliance with GLBA doesn't exempt you from other privacy regimes—duties stack.

- NPPI coverage extends far beyond banks. Fintechs, retailers with credit programs, auto finance companies, law firms, and vendors all handle NPPI. If you process financial data on behalf of covered institutions, you're contractually—and often regulatorily—required to protect it.

- The FTC Safeguards Rule is mandatory and enforceable. Covered financial institutions must implement written information security programs with specific required elements: risk assessments, access controls, encryption, vendor management, monitoring, and incident response. While the rule allows for risk-based tailoring to an institution's size and complexity, the core requirements are not optional—they're enforceable by the FTC.

- Breaches of NPPI trigger multiple notification obligations. The FTC requires non-bank financial institutions to report certain breaches within 30 days. State laws add consumer notification and sometimes state regulator reporting. Contracts with financial institution clients impose additional notice requirements. Missing any deadline creates liability.

- Visual redaction doesn't satisfy GLBA safeguards requirements. Black boxes and deleted text in documents often leave NPPI in metadata, version history, and embedded objects. To effectively comply with GLBA's requirement to protect the security and confidentiality of customer information, organizations must ensure permanent removal—not cosmetic hiding—before documents are shared, archived, or disclosed.

- Classification drives compliance. If you don't recognize data as NPPI, you won't apply the right controls. Tag NPPI distinctly in data inventories, map it to GLBA obligations, and train staff to spot it in unstructured data like emails, scanned documents, and shared files.

The regulatory environment around financial data is tightening, not loosening. State privacy laws are expanding, the CFPB is encouraging more comprehensive regulation, and the FTC is enforcing Safeguards Rule violations more aggressively. Organizations that treat NPPI as a compliance checkbox instead of an operational discipline will face the consequences: penalties, breach notifications, and loss of trust.

Ready to protect NPPI with compliant redaction workflows? Redactable's AI-powered platform automatically detects NPPI across 40+ sensitive data categories, performs permanent redaction with guaranteed metadata removal, and generates compliance certificates for audit trails - delivering 98% time savings compared to manual redaction. Start your free trial or schedule a demo to see automated NPPI protection in action.