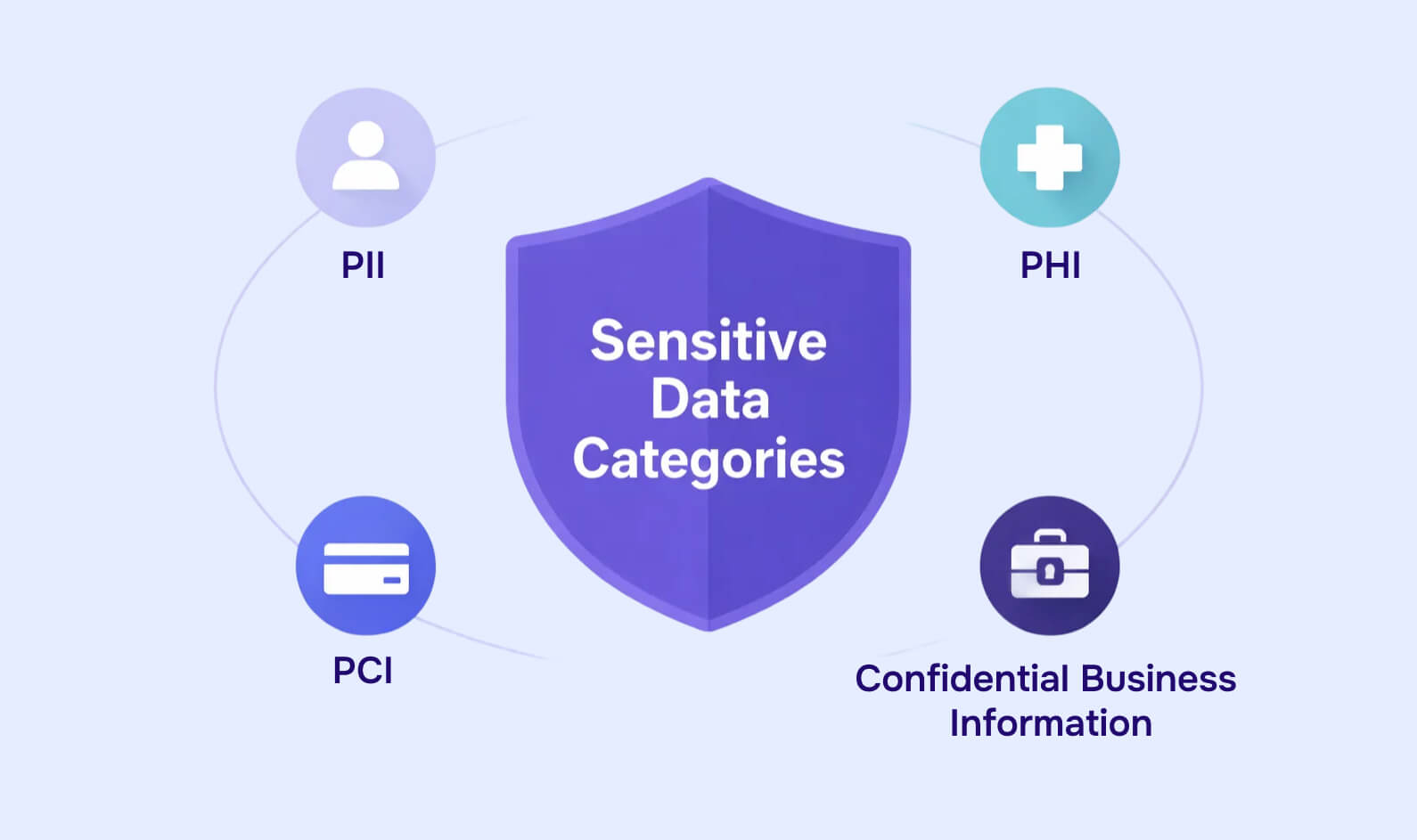

Not all data breaches carry the same weight. Losing a marketing email list triggers different consequences than exposing medical diagnoses, full credit card numbers, or whistleblower identities. Understanding which types of sensitive information you handle - and the legal obligations attached to each - determines whether your response is a minor incident report or a career-ending regulatory penalty. This guide breaks down the four core categories of sensitive data (PII, PHI, PCI, and confidential business information), shows you what separates "ordinary" from "high-impact" data, and explains exactly when redaction stops being optional.

The difference between a contained data incident and a catastrophic breach often comes down to one question: what kind of information was exposed?

A leaked list of newsletter subscribers might cost you some trust and require disclosure. A spreadsheet containing Social Security numbers, cancer diagnoses, or full payment card data can trigger federal investigations, million-dollar fines, and class-action lawsuits. Same "data breach" label, radically different outcomes.

Here's what most organizations miss: NIST explicitly states that "all PII is not created equal." Federal agencies must classify personally identifiable information as low, moderate, or high impact based on potential harm. GDPR takes it further, flatly prohibiting the processing of "special categories" like health data, biometrics, and political opinions unless narrow conditions are met. HIPAA defines 18 specific identifiers that transform health information into protected health information, triggering strict safeguards and penalties that can reach or exceed $1.5 million per violation category per year, with caps adjusted periodically by HHS.

By the end of this article, you'll be able to recognize the main types of sensitive data in your systems, understand which laws and contracts attach to them, and know when redaction becomes mandatory - not just best practice.

What counts as sensitive data and who decides?

Sensitive data is any information whose unauthorized access, use, or disclosure could cause harm to individuals or organizations. That definition comes from NIST's focus on confidentiality impact and GDPR's standard of "likely to result in high risk to rights and freedoms."

But here's the nuance that trips up most teams: sensitivity is context-dependent.

An email address on a public blog post carries low risk. The same email address in a database of domestic violence survivors, HIV patients, or confidential informants becomes high-impact data requiring encryption, access controls, and aggressive redaction before any disclosure.

This is why data classification frameworks distinguish between:

- Intrinsic sensitivity: Data that's inherently risky regardless of context (biometric templates, genetic markers, full Social Security numbers)

- Sensitivity by linkage: Seemingly innocuous data that becomes identifying when combined (date of birth + ZIP code + gender can re-identify individuals in 87% of cases)

The practical consequence: you can't treat all information the same way. A one-size-fits-all approach to data protection leaves you exposed where it matters most and wastes resources on data that carries minimal risk.

The four core types of sensitive data

1. Personally identifiable information (PII)

PII is information that can distinguish or trace an individual's identity, either directly or through linkage with other data. This is the broadest category of sensitive information and the foundation for most privacy regulations.

Direct vs. indirect identifiers

Direct identifiers immediately reveal identity on their own:

- Full name combined with Social Security number

- Driver's license or passport number

- Biometric records (fingerprints, retinal scans, voice prints)

- Full-face photographs tagged with names

Indirect identifiers become identifying in combination:

- Date of birth + five-digit ZIP code

- Gender + race + occupation + company size

- Timestamps + location patterns from mobile devices

- Purchase history combined with demographic data

Here's the compliance trap: regulations don't just cover direct identifiers. HIPAA's "safe harbor" de-identification standard requires removing 18 categories of identifiers, many of which are indirect. GDPR explicitly addresses "identifiable" individuals, not just "identified" ones.

"Ordinary" vs. sensitive PII

Not all PII carries the same risk. NIST explicitly states that organizations should rate PII as low, moderate, or high impact depending on potential harm if exposed:

- Low impact: Business contact information, general demographic data already public

- Moderate impact: Personal email addresses, dates of birth, employment history

- High impact: Government IDs, financial account numbers, biometric data, detailed behavioral profiles

The distinction matters for technical controls. High-impact PII should be encrypted at rest and in transit, restricted to need-to-know access, and permanently redacted from any documents leaving your secure environment - not just visually masked with black boxes.

2. Health and genetic data (PHI and special category data)

Health information sits at the top of the sensitivity hierarchy because exposure can lead to discrimination, denial of insurance, employment consequences, and profound privacy violations.

PHI under HIPAA

Protected Health Information (PHI) is individually identifiable health information held by a covered entity or business associate, in any form -electronic, paper, or oral - relating to:

- Past, present, or future physical or mental health conditions

- Provision of healthcare to an individual

- Payment for healthcare services

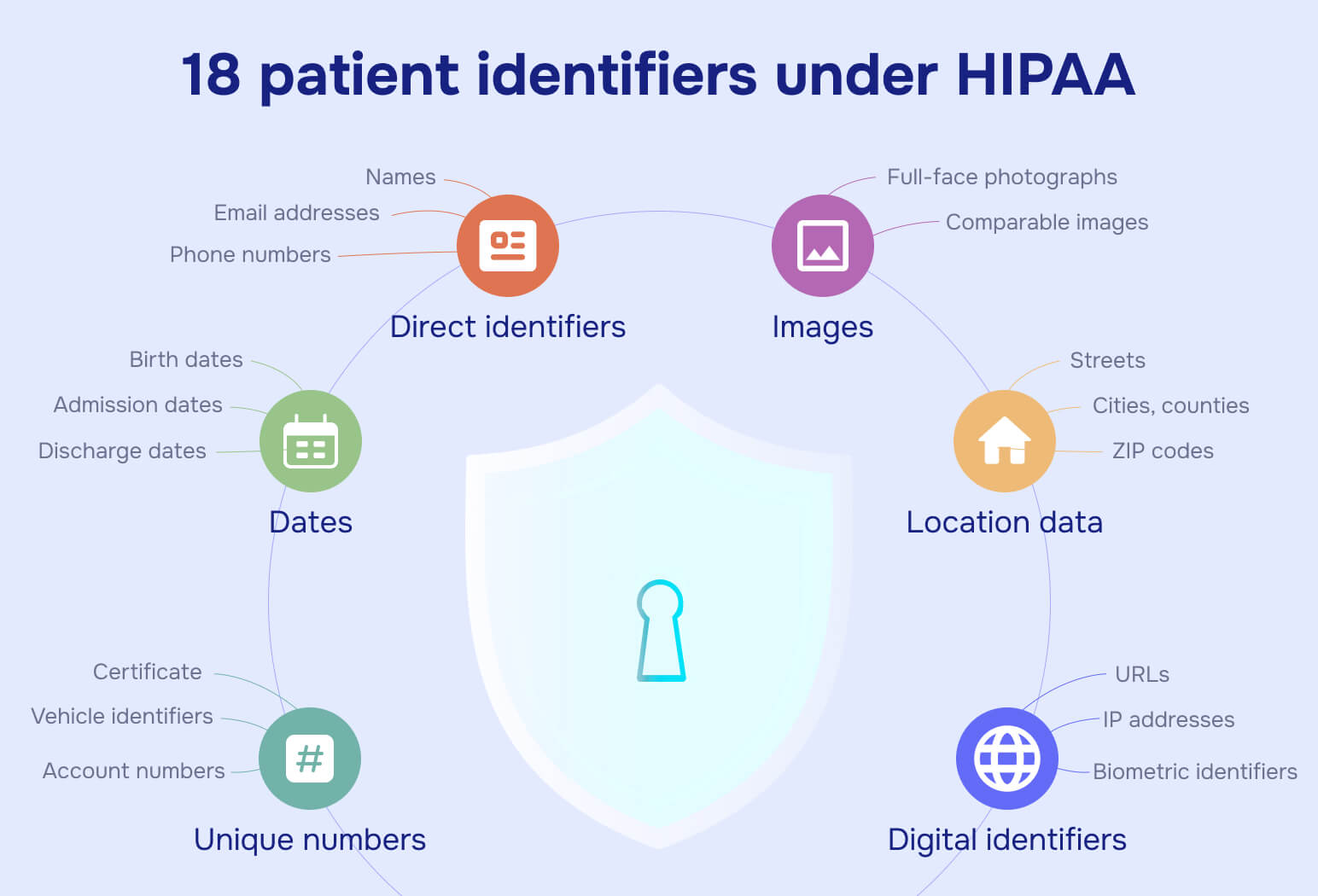

What makes health data "protected" under HIPAA? The presence of any of 18 specific identifiers attached to health information:

- Names

- Geographic subdivisions smaller than a state (street addresses, cities, counties, ZIP codes)

- Dates (birth, admission, discharge, death, or exact ages over 89)

- Phone numbers

- Fax numbers

- Email addresses

- Social Security numbers

- Medical record numbers

- Health plan beneficiary numbers

- Account numbers

- Certificate or license numbers

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers

- Device identifiers and serial numbers

- Web URLs

- IP addresses

- Biometric identifiers

- Full-face photographs

- Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code

The penalties for mishandling PHI are severe. Violations are tiered based on knowledge and intent, with annual maximum penalties reaching $1.5 million per violation category. And unlike many regulations, HIPAA's enforcement arm (OCR) has shown consistent willingness to investigate and fine organizations of all sizes.

Health data under GDPR

GDPR Article 9 classifies "data concerning health" and genetic or biometric data used for unique identification as "special categories" that are generally prohibited to process unless specific conditions are met (explicit consent, vital interests, employment law, substantial public interest, etc.).

This creates a compliance gap that catches US-based companies: HIPAA covers healthcare providers, health plans, and their business associates. GDPR covers anyone processing health data of EU residents, regardless of industry. An HR department handling employee medical leave records, a fitness app tracking biometric data, or a research institution analyzing genetic samples all fall under GDPR's stricter standard.

The redaction implication: health records released for research, shared in litigation discovery, or disclosed in response to subject access requests must be rigorously de-identified. Visual redaction tools that leave underlying text searchable don't meet the standard. You need permanent removal of identifiers and metadata.

3. Financial and payment card data (PCI)

Financial information carries dual risk: direct monetary theft and long-term fraud enabled by stolen credentials and account details.

Cardholder data under PCI DSS

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) defines two critical categories:

Cardholder data includes:

- Primary Account Number (PAN) – the full card number

- Cardholder name

- Expiration date

- Service code

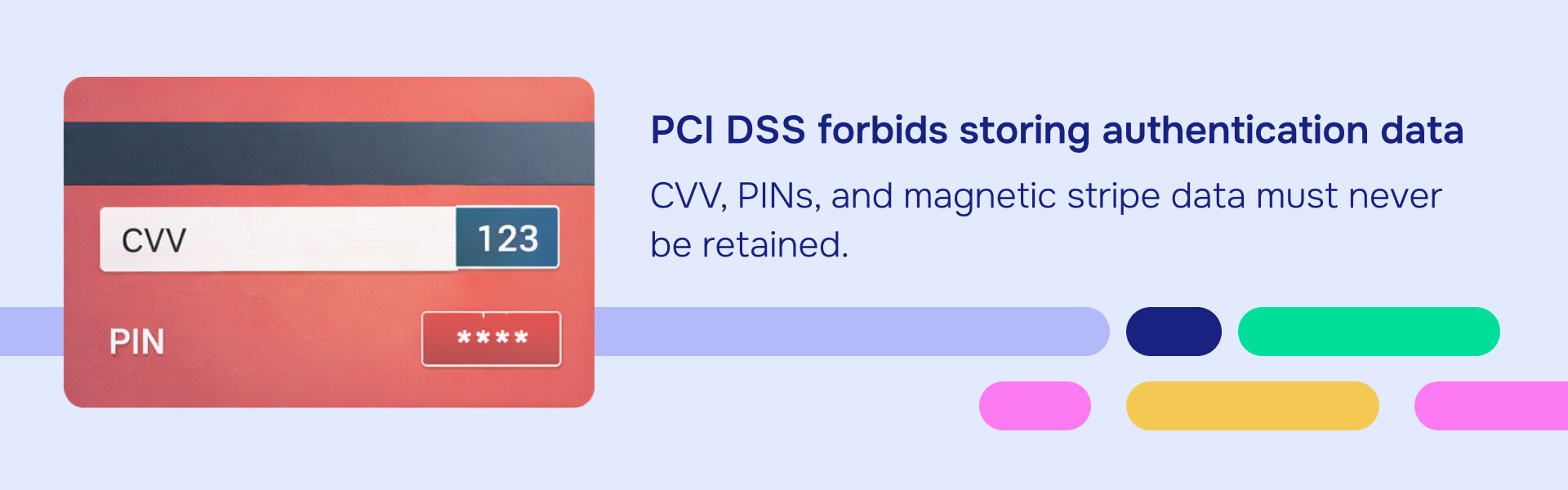

Sensitive authentication data (which must never be stored after authorization):

- Full magnetic stripe data

- CAV/CVC/CVV/CID security codes

- PINs and PIN blocks

Here's the enforcement reality: PCI DSS isn't a law, it's a contractual obligation enforced by payment brands (Visa, Mastercard, etc.). Non-compliance can result in fines that can reach tens of thousands of dollars per month, higher transaction fees, and even loss of payment processing privileges.

Why partial exposure still matters

Even truncated or masked card data combined with other information creates fraud risk. A support ticket showing the last four digits of a card number, plus the cardholder's full name, email address, and billing ZIP code, gives bad actors enough information for social engineering attacks or account takeovers.

This is why PCI DSS requires strict controls on cardholder data in all forms: payment processing logs, customer service screenshots, emailed receipts, and CSV exports. If you're sharing documents that might contain payment information, permanent redaction with guaranteed metadata removal isn't optional.

Special category and high-risk personal data under GDPR

Beyond health data, GDPR Article 9 identifies several special categories of personal data that require exceptional handling:

- Racial or ethnic origin

- Political opinions

- Religious or philosophical beliefs

- Trade union membership

- Genetic data

- Biometric data for unique identification (facial recognition, fingerprints)

- Data concerning sex life or sexual orientation

Why the heightened protection? Because misuse can cause discrimination, denial of services, persecution, physical harm, or social stigma.

Real-world examples:

- Political donation records used to target individuals for harassment

- Facial recognition logs that reveal attendance at protests or religious services

- Employment records showing union membership in anti-union jurisdictions

- Healthcare data revealing HIV status, mental health treatment, or reproductive history

These aren't theoretical concerns. Companies have faced multi-million euro fines for inadequate protection of special category data, often because redaction workflows failed to remove metadata or relied on visual masking that left sensitive information embedded in file properties.

4. Confidential business and operational data

Not all sensitive data is personal information. Organizations also handle business-sensitive data that, while not regulated under privacy laws, carries significant competitive and legal risk.

Trade secrets and commercially sensitive information

Trade secrets are information that derives independent economic value from not being generally known and is subject to reasonable secrecy measures. Examples include:

- Proprietary source code and algorithms

- Pricing strategies and customer lists

- Manufacturing processes and formulas

- Negotiation strategies and M&A documents

- Security architecture and incident response playbooks

- Competitive intelligence and market analysis

Exposure doesn't just harm competitive position - it can eliminate trade secret protection entirely under the law. Once disclosed without adequate confidentiality measures, trade secret status may be lost permanently.

Internal classification levels

Many organizations adopt classification frameworks inspired by government and NIST models:

- Public: Information intended for public disclosure (marketing materials, published reports)

- Internal: Information for internal use but not highly sensitive (general policies, org charts)

- Confidential: Information that would cause significant harm if disclosed (business strategies, employee data, contract terms)

- Restricted: Information that would cause severe harm if disclosed (authentication credentials, encryption keys, security vulnerabilities, customer financial data)

Restricted data often includes technical secrets that must never appear in logs, support tickets, or code repositories without redaction:

- Database connection strings with embedded credentials

- API keys and OAuth tokens

- Encryption keys and certificates

- Privileged account passwords

- Security vulnerability details before patches are deployed

The compliance gap: these items might not fall under HIPAA, PCI DSS, or GDPR, but contractual obligations (NDAs, service agreements) and liability exposure (negligence claims, trade secret theft) still require strict handling.

Bringing it together: A sensitivity decision matrix

Use this framework to assess your data:

Frequently asked questions

The four core types of sensitive data are: (1) Personally Identifiable Information (PII), including direct and indirect identifiers; (2) Protected Health Information (PHI) and health data under HIPAA and GDPR; (3) Payment Card Industry (PCI) cardholder data and financial information; and (4) Confidential business data, including trade secrets, credentials, and restricted operational information. Each type carries different legal obligations and requires specific technical controls.

NIST explicitly states that "all PII is not created equal." Ordinary PII (business contact information, general demographics) poses low to moderate risk if exposed. Sensitive PII (Social Security numbers, biometric data, government IDs, detailed behavioral profiles) poses high risk, including identity theft, fraud, and physical danger. Sensitive PII requires encryption, strict access controls, and permanent redaction before any external disclosure.

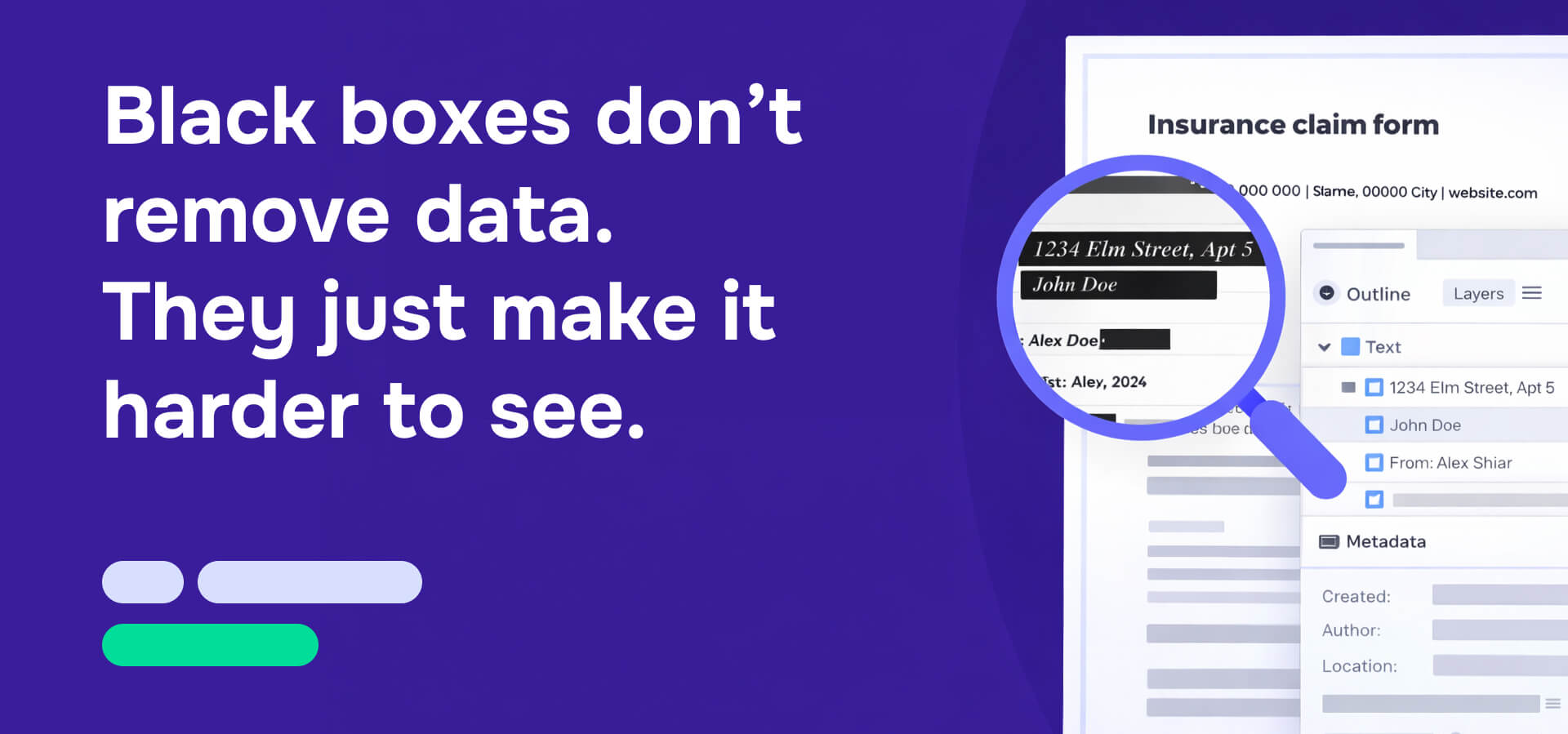

Visual redaction with black boxes or blurred text doesn't remove sensitive data from the file - it only hides it. The underlying text often remains searchable and copyable. PDF metadata preserves author information, revision history, and editing details. Hidden layers, transparent objects, and content outside page boundaries can leak sensitive information. NIST, HIPAA, and GDPR standards explicitly require permanent removal of sensitive data, not cosmetic masking.

Access control limits who can see data within your systems. Redaction permanently removes sensitive elements from documents that must be shared externally or preserved for legal reasons. Redaction becomes required when: (1) responding to FOIA requests or subject access requests, (2) producing documents in litigation discovery, (3) sharing research datasets, (4) releasing medical records to third parties under HIPAA, (5) providing audit evidence containing sensitive operational data. Access controls alone fail when documents leave your environment.

Consequences depend on the data type and applicable law. HIPAA violations can reach $1.5 million per violation category annually. PCI DSS non-compliance results in fines of $5,000 to $100,000 per month and potential loss of payment processing ability. GDPR violations can reach €20 million or 4% of global annual revenue, whichever is higher. Trade secret mishandling can eliminate legal protection permanently. Beyond fines, expect breach notification costs, legal fees, reputation damage, and class-action exposure.

More About

Data Privacy

Ready to get started?

No credit card required

Start redacting for free

Cancel any time